The Fourth Crusade: Act III

The Price of Devotion: How Venice Turned the Crusade on its Head

You’ve returned.

Good.

You will want to be present for the next Act- after all who doesn’t love a little math, money, and a devastating mountain of debt?

But before we begin, if you have somehow found your way here and seem to be lost, you can catch up by reading the previous act.

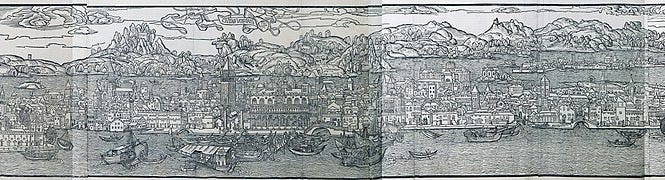

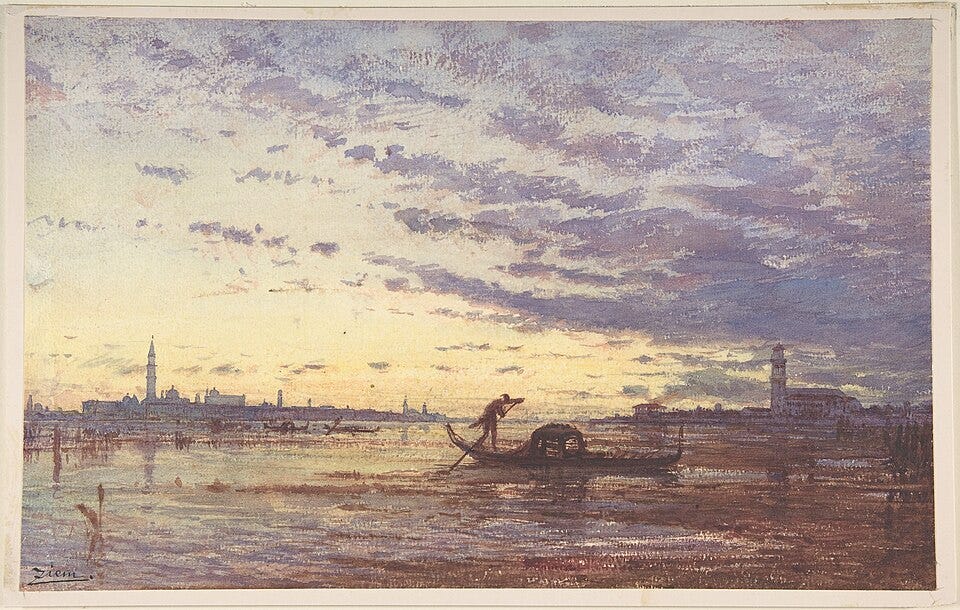

We arrive back in Venice on calm waters. As we dock, the sun shines and the city seems to smile back at us as we step onto the dock.

But this perfect day is a lie- for soon, alongside the Crusaders, we'll find ourselves ensnared by promises that were never meant to be kept.

The only escape will be a compromise that dooms an entire city to a fate of death, betrayal, and blood.

So bask in the glow of the sun while you can, sit with me, and let us continue our tale.

The Root of The Problem

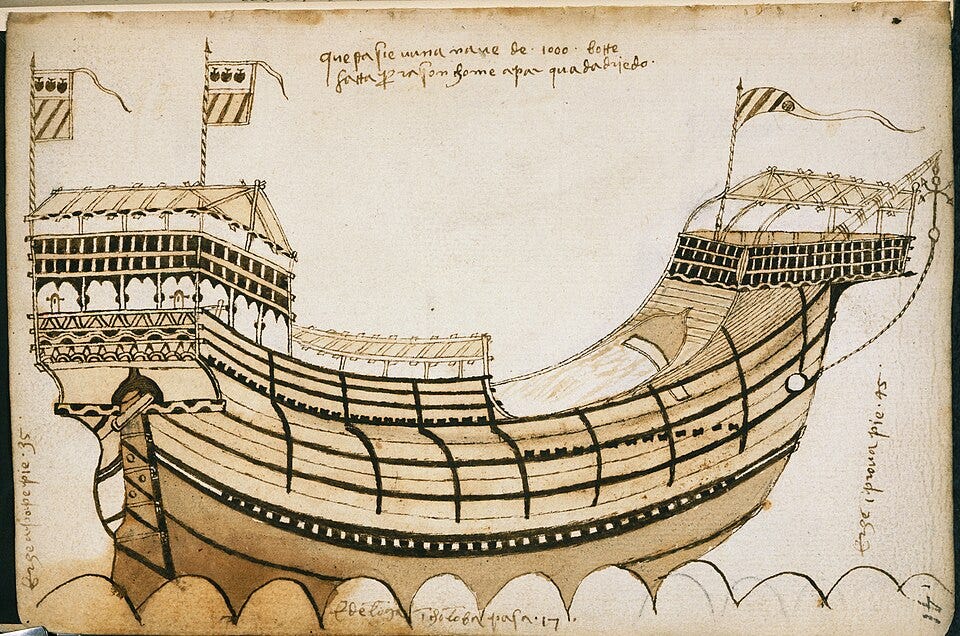

Building a ship requires skill and a lot of resources. At the turn of the thirteenth century, there were not many places which could handle the sheer magnitude of labor and materials needed to build a fleet of six hundred ships.

But Venice could.

For a price.

When the Crusaders met with the great Doge of Venice, he assured them with a bright smile on his face and a twinkle in his eye, that yes, Venice could and would build the Crusaders their fleet of ships.

The Price? 85,000 Silver marks.

This is not 85,000 US Dollars or Euros or whatever Canada uses1. To convey the weight of the sheer amount of wealth that Venice was demanding, I will give you a little lesson on Venetian coinage and math2.

Before the Venetian Grosso, there was a smaller silver coin called the denier. Without going too far into the Italian Economy in the thirteenth century (and I can, trust me), a single denier in 1201 would be able to buy you a loaf of bread (Plain white bread, not gluten free, not vegan, and free of mold).

1 Denier = 1 loaf of bread

If you remember though, our dear old Doge had the Venetian Grosso minted in 1191. This was a heavier coin, weighing in at 2.18 grams of silver to the .3 of the denier. The conversion (if you are like me and your math skills are not, shall I say…good), was roughly 26 denier to one grosso.

1 Grosso = 26 Denier = 26 loafs of Bread

A silver mark is not a coin, it is a unit of account and (in 1201) was 230 grams of silver, around 105 grosso.

1 Silver Mark = 105 Grosso = 2,730 loafs of bread

Which means…

85,000 Silver Marks = 8,925,000 Grosso = 232,050,000 loafs of bread

Over two hundred million loaves of bread, you can’t even picture that much bread, let alone comprehend. That’s okay, clearly the Crusaders couldn’t either.

Still not getting it? Let me help.

For this scenario, I will give you the benefit of the doubt and call you a skilled laborer. Your actual skills (or lack thereof) are useless, but your new carpentry skills are impressive. So impressive that you make more than your normal, cut of the mill, chair making carpenter.

No, you are a ship building carpenter. And those skills are about to come in really handy.

The all-generous Doge of Venice is going to pay you 8 denier a day to help take on this massive undertaking. Assuming you are like the rest of the Venetian workforce, you work six days a week minus holidays, down time, feasting, etc. This accounts to an average of 288 days of working a year (subject to the stray plague here and there).

Your annual salary would be 2,304 deniers. That seems like a lot to you, it allows you to have a small hobble to raise your children in, it allows your wife to buy shoes every couple years, and you eat quite a bit of bread.

Life is good.

But let’s now say that you decided to cover the cost of the Crusaders’ fleet, all 85,000 silver marks.

It would take you 100,648.44 years to make enough money to pay for the fleet of ships.

This is assuming you don’t have any other expenses (i.e eating, water, home payments).

For context, if you lived to seventy, it would take you 1,437 lifetimes to pay the crusaders debts.

It was an unGodly amount of money.

Held Hostage by Promises of Silver

Boniface and Baldwin had expected over thirty-three thousand men to appear in Venice, which justified the need for such an enormous fleet of ships. Their plan was to pay Dandolo once the men arrived, since the crusades were essentially a pay-to-play enterprise.

Reality came in the form of less than fifteen thousand men arriving in Venice, ready to set sail.

Now you dear reader, being as smart as you are, know that in order to sail, you need a boat. And the crusaders were about to have an abundance, right?

Not exactly. You see, while the ships were ready, the money had yet to be paid. And the Crusaders were stranded on Lido, completely reliant on the Venetians for food, drink, and transportation.

Now I don’t think Boniface woke up with a severed horse head in his bed, but I am sure the stark chill of fear made its way down his body when he realized that he and the rest of the crusaders were not just unable to pay, but they were also trapped on an island with no way off3.

Before you feel bad for them, I want you to remember your life as a carpenter. Your boss has to have the money to pay you, and his boss has to have the money to pay him, and at some point, when you get to the top, and there is no money?

The entire column collapses4.

Doge Enrico Dandolo had a pickle on his hands, and it was a big one with lumps and bumps. The proposal was this,

Venice would lend the crusaders the rest of their 34,000 silver marks that they were owed, and they would expect to be repaid from the spoils of the crusade.

However, there was a catch.

Zara.

I told you that we would return.

Zara had once been a part of the Venetian republic, but in 1183 they had rebelled and put themselves under the protection of Hungary and the Pope. Dandolo proposed that the crusaders take the city under heel and return it to the Venetians.

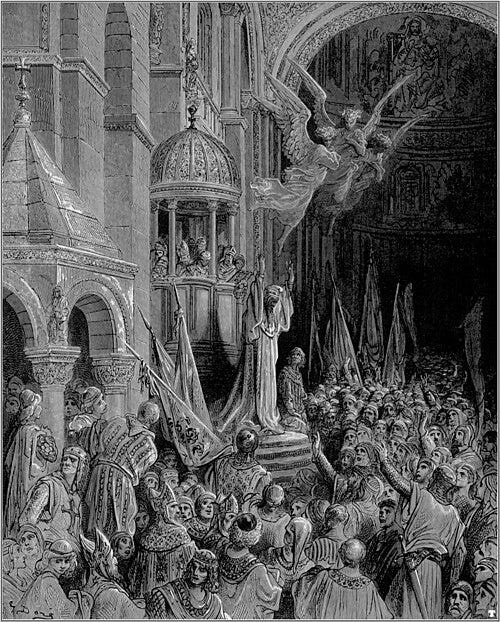

As you can imagine, many of the crusaders were hesitant or downright outraged. It wasn't just politically risky, it was sacrilegious. Zara was publicly under the Pope’s protection.

So, you see, when Dandolo demanded the siege, he was asking for more than blood, he was asking men to go against God’s Will.

But sometimes you don’t have many choices, and Boniface and Baldwin’s were rapidly dwindling.

The Doge publicly took the cross in St Mark’s Basilica, binding Venice to the crusade with his vow. In October 1202, the fleet sets sail.

After nearly a month at sea, Enrico Dandolo strides onto the deck of his massive war galley, ten thousand of his own men at his back. Despite his failing eyesight, he stares down the shores of a city about to be betrayed by men they had once called brother.

Ahead lies Zara, the sun glinting off the gilded rooftops, the city unsuspecting of the storm about to crash against their gates…

The Fourth Crusade has just begun

Next Up… Let’s siege a city.

Thank you for reading Act III. I have done my very best to make sure the information given is historically accurate, however if you have any notes/corrections, feel free to share.

My goal is to make historical events, people, and places assessable and interesting for those who love history and those who think of it as a chore worse than doing the dishes.

If you would like to support this page, you can subscribe, share the story, and donate if you wish.

They use the Canadian Dollar. In case you were wondering. I know I wasn’t.

I hate this as much as you do. Math is the BANE of my existence. But bear with me, it is about to get very…delicious and filled with gluten.

I really wanted to name this chapter ‘Trapped in an Island, but not with Josh Hutcherson’ but I was afraid no one would get the reference. Jenny Nichols did a video years ago about a fanfiction on Wattpad, and to this day, I am still not over it.

Remember, Venice as a LOT of collums.

Was not expecting the Canadian slander 😂😂